Anatomy of Melancholy

- Tokyo Cine Mag

- Dec 30, 2025

- 4 min read

A Review of the Short Film The Conversation

Every work of art constructs its own universe, and the manifestation of reality differs from one film to the next. The "reality" of a work begins with its opening shots: the depiction of environment and character, the texture of the dialogue, the relationship between the individual and society, and the myriad details—intentional or otherwise—that a filmmaker weaves into the fabric of the piece. It is through these specific details that we come to recognize a film’s world.

The spectator enters into a contract with the film based on these established details. According to this agreement, whatever the filmmaker defines as reality is accepted by the audience—whether it be a tale set in the distant future, a story of ancient cave-dwellers, or a fable of mythical creatures. Ultimately, the most crucial point is not how the work correlates with our daily lives or what we see on the street; rather, it is whether the filmmaker succeeds in advancing their constructed reality and building meaningful resonance within it.

Carlo Caiazzo’s short film, The Conversation, is certainly not a work of conventional realism. From the opening dialogue and our first encounter with its atmosphere, the film reminds the viewer that they are engaging with a mental, abstract, and non-realist work—a purely conceptual piece that builds its own unique world. Caiazzo, who also serves as the writer and lead actor, demonstrates how one can produce an independent film within a confined space and with limited tools to precisely articulate complex ideas.

The Conversation is noteworthy from several perspectives, particularly in its creation of a bespoke reality. We accept a world where an individual is in dialogue with himself, rendered as a literal conversation between two distinct personas. Through this technique, the filmmaker unmasks the involuntary and subconscious aspects of the mind, inviting the audience to reconsider the very concept of internal monologue.

While the filmmaker reveals his hand early on—making it clear that we are witnessing an internal dialogue—he is astute enough to know that in a "cinema of ideas," the concept itself is secondary to its execution. What matters is how the idea is expanded, where it leads, and how the trajectory is mapped out for the spectator. In Caiazzo's hands, this internal dialogue is thoroughly explored, weighing its various dimensions and probing its diverse angles. The film examines the complex duality an individual maintains with their inner self, where conflicting beliefs often possess deep psychological roots in one's past. At times, this duality points toward simultaneous, contradictory emotions regarding a single situation—such as the paradox of self-love and self-hatred—which can intensify in conditions like depression or borderline personality disorder.

Another significant feature is the quality of the acting. Caiazzo takes a considerable risk by placing himself in a position where he must simultaneously portray two distinct and vital roles. He must differentiate between the two characters while simultaneously capturing their commonality, as both are ultimately two sides of the same coin. This is a delicate and difficult task; failure here would have dismantled the entire film. However, Caiazzo successfully maintains this balance between difference and unity, delivering a thoroughly convincing performance.

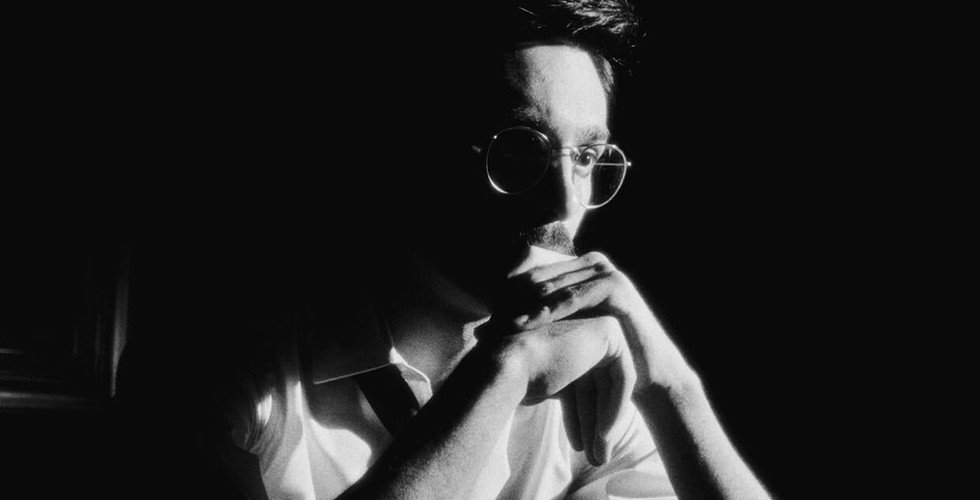

Visually, the director achieves a sense of grandeur. The cinematography—spanning framing, lighting, and general aesthetic—is excellent. Despite being restricted to a closed environment, the filmmaker maintains visual variety, exhibiting a sense of creative freedom born from a precise understanding of découpage and scene construction. This meticulous visual work effectively evokes the atmosphere of Film Noir, a difficult feat to achieve in a short film.

The film utilizes high contrast, low-key lighting that creates long shadows and sharp edges, and the "Dutch Angle" to instill a sense of instability, vertigo, and insecurity within the protagonist's world—all hallmarks of the Noir genre. Beyond these visual tropes, the film moves toward Noir conceptually through its treatment of the anti-hero. The filmmaker constantly shifts the role of the anti-hero between the two characters; as they swap places, we are confronted with new layers of human psychological complexity.

The anti-hero here is not necessarily a villain, but lacks traditional heroic traits such as unwavering courage, purity, or absolute self-sacrifice. Instead, the characters are portrayed with human flaws, hesitations, and occasionally selfish motives. Caiazzo’s work is significant because these two characters exist in the space between virtue and vice. They may appear cynical, fearful, or deeply damaged, and their positions shift during the course of their conversation. The audience can easily empathize with them because their behavior reflects the reality of human nature—a blend of right and wrong.

The Conversation is a sophisticated work full of structural nuances. It tackles the sensitive subject of suicidal ideation through a thoughtful, non-judgmental lens. It successfully avoids the common cinematic clichés surrounding depression and suicide, establishing its own unique perspective and achieving a consistent, independent tone.

Admittedly, it is a difficult film to watch. It refuses to pander to the audience, choosing instead to confront its subject matter with unflinching honesty. Consequently, some may find the film bitter, but this bitterness is neither forced nor performative; it is a "philosophical bitterness" inherent to the situation, the character, and the theme. Ultimately, The Conversation is a successful endeavor in independent filmmaking, navigating a complex and difficult subject with remarkable poise.

Comments